In a few days, I will be running from the Sea to Summit of Mauna Loa. Entertainingly I expected this adventure to be significantly more difficult than the Sea to Summit of Mauna Kea. I will also be doing this run completely self-supported. In this article, I’ll explain what makes this such a difficult route, how I trained for the route, why I want to do it self-supported, and finally how long I expect the route to take.

Why So Hard?

Any runs from the ocean to the summits of Mauna Kea or Mauna Loa are going to be extremely hard. What makes them really hard isn’t just the continuous non-stop uphill, or having gear prepared for anything from hot sea level temperatures to snow. What really makes them hard is going from 0 to near 14,000 feet with no acclimatization. As the day progresses and you get higher your body is tired from hours of hard effort. But on top of that, there is less and less oxygen absorbed in every breath you take which becomes very apparent at just 5,000 feet when your body only takes in 84% of the oxygen that was down at the ocean. By 10,000 feet the oxygen absorption has slowly lowered to 70% of sea level. By 13,000 feet you are taking in 63% of sea level oxygen. And Wow is that apparent! A 10 minute/mile uphill pace down near the ocean can turn into a near 25min/mile pace at 13,000 very easily. So I’ve basically discovered that 50-60 miles of running isn’t that hard even if there are a lot of hills. It’s when you make it just 1 hill and all day long you just keep taking away a little bit more oxygen that the run turns into a very different level of difficulty.

A Sea to Summit run of Mauna Loa from Chain of Craters Road serves up even more challenge though on a few fronts. Just getting to the start or finish points for training runs from my home in Palisades, Kona was 90 min (top of Mauna Loa Observatory Road) to 2.5 hours (bottom of Chain of Craters Road) each way. Also, although this Sea to Summit route of Mauna Loa is around 53 miles (similar to the 55 miles for Mauna Kea Sea to Summit from A-Bay), the final 20 miles are all off-road. It is going to be a no-support zone along this section that leaves Mauna Loa Road at 6600 feet and gains over 7000 feet to summit at 13,678 feet. The trail is often just meandering over pahoehoe and a’a flows where there really is no trail but Ahus (cairns – stacks of piled rocks) every 50 to 200 feet as a visual clue of where to go. So after roughly 34 miles and 6600 feet of elevation gain I need to be able to get into autopilot and push my mind and body through this section. If clouds, fog, rain, or snow come in along the way I need to feel solid that I can get to the summit or turn around and find my way back to the top of the Mauna Loa Road. Also, you are at higher elevations for longer than on Mauna Kea. On Mauna Kea, I move from 10,000 to the 13,803 feet in around 7 miles. On Mauna Loa from 10,000 feet to the summit at 13,678 is 12 miles. That is 5 miles more above 10,000 feet and all on lava flows and not a paved or gravel road.

Then to top it all off, once I reach the summit I still need to cover 6.2 miles and 2,700 feet of descent over the same type of “trail” as described above (walking it will take over 3 hours). That is an entire unsupported offroad marathon (26.2 miles) at elevation to wrap up this run! Needless to say, this challenge is a whole other level above Mauna Kea.

Below is a public map I created to give everyone the exact route I will follow. I’ve added notes to the map so my wife and family know what to expect.

Mauna Loa’s summit elevation is 13,678 feet but the entire elevation gain I should cover will be approximately 14,072 feet (basically there is around 400 feet of loss along the route). I have the distance predicted from my past GPS captures as 53 miles up and then 6.2 miles down to the Mauna Loa Observatory. I create maps like this with past GPX files that my Garmin 935 watch captures when I do the runs. I then import the files into Google Maps and have exact GPS data. I then don’t need to rely on trail maps that are often incorrect on this island. Also in a complete whiteout, I can follow the route by phone with no cellular connection needed – though for that I use the Gaia app with all the same data as Google Maps (and a bit more).

Of course, this is actually the challenge I’ve been looking for. The Big Island’s backcountry is spectacular yet brutally hostile for the unprepared. When you add into the mix: elevation, mother nature, and being physically, mentally and emotionally taxed, you wind up with a seriously worthy challenge to find in your own back yard. So to mitigate the risks I created a detailed plan of training where I wound up covering the entire backcountry trail in both directions. During these runs, I had multiple tasks I needed to accomplish such as: creating GPS waypoints to follow if blinded by weather, testing out gear and nutrition, practicing being a camel with my water, spending running time at altitude, but most of all I’ve been “Feeling” out the route. I need to be able to trust my intuition and just know which way to go even when exhausted. At the end of the day, technology fails, gear breaks, mother nature does her worst; and all that you are left with is a trust that you intrinsically know where to go or when to turn around. And that feeling only comes from repetition.

How I Trained

So to accomplish this Sea to Summit run I broke the entire route into 3 sections of somewhat equal difficulty. I spent a few weeks going up to the summit and upper areas of Mauna Loa. I called this the Upper Section and you can find articles on training in this area here: (28 Miles Above 11,000 feet, Observatory to Summit Exploring). I then spent a day exploring the Volcano Village area and a few days later ran the Sea to Summit of Kilauea. I called this the Lower Section and you can find details here: (Exploring through Kilauea, Sea to Summit – Kilauea). Finally, I covered the Middle Section last week that takes you through the rainforest section into full alpine and raw unvegetated lava: (The Middle Section).

What is Self-Supported and Why?

Self-supported means I receive no aid from anyone except to drop me off and pick me up. I can set up caches but receive no aid from others. This means that someone will drop me off at the bottom of the Chain of Craters Road and then pick me up 20 or so hours later at the Mauna Loa Observatory parking lot (90 miles away by car). No help in between. I will have 1 water and gear stash at 22 miles into the run at 4,000 feet. I will also refill my water at the Red Hill Cabin 18 miles later at 10,000 feet. And that is it. If all goes well I may not see another human being for that entire time.

I’ve chosen this style because honestly with a midnight start there was only one place I would have even wanted support and that was 34 miles into the run at the top of the Mauna Loa Lookout. But my last run showed I could comfortably travel from the bottom of the Mauna Loa Strip road (22 miles in) to the Red Hill Cabin on one water supply. And my gear handled being wet the whole time. So why have a person waiting around for me for hours just to give me a little water and gear one time? I expect I’ll also get soaking wet early and down low on the route. But I have the confidence in my gear that it’ll still be functional when wet and above 13,000 feet. So dry gear might have been handy 34 miles into the run but I can live without it.

Ultimately I love the soul searching aspect of being alone, self reliant, and pushing my limits mentally and physically. You need to dig a bit deeper. Analyze the risk/reward factor more frequently. And you are forced to treat the adventure like there will be no rescue. You can’t just collapse 15 miles into the trail at 12,000 feet and hope someone will come and get you. That’s not really an option. Honestly, I think this raw self reliance is one of the biggest draws to this run.

Running Strategy

After running Mauna Kea from Sea to Summit two months ago I discovered a weakness in my overall conditioning and gameplan that I needed to address for this run. Knowing I had a mobile aid station for the last 20 miles I overall pushed harder than I should have with the idea of setting a fast(ish) time for the run. But I had not accounted for the headwind being as strong and continuous as it was for 40 miles and I really should have backed off. For that section which took near 10-hours, I had an average of 141bpm heart rate. My fitness dictated (as I would see from the data later) that I should have been more like 135bpm or less for that timeframe. At near 14 hours into the run, I could not get my heart rate above 130bpm. And an hour later no higher than 120bpm. I did not technically have the fitness to cover this next section of 3.5 miles above 12,000 feet and 1,750 feet of elevation gain with any speed. So I was ground down to a 40min/mile pace with an average Heart rate of 113bpm. I could permit that to happen when I had the safety net of a support van right nearby. But on the Mauna Loa run it would not be wise to be in the last miles and be that worn out. And more critically: I need the energy to descend to the van at the observatory 6.2 miles from the summit.

In rock climbing one of the most committing forms of adventures is climbing a Big Wall or mountain in one continuous push known as fast and light ascents or speed ascents. When you learn to do it in Yosemite on El Capitan you get to practice how to conserve enough energy to finish let’s say a 24-hour push to the top of a route, with the most minimal of gear, and then spend the next few hours casually/carefully hiking and rappelling back down to the valley floor. Out in the serious mountain ranges of the world when you take these techniques and translate them onto mountains where there will never be a rescue, you learn that the summit is nowhere near the completion of the climb. In fact, most deaths happen on the descents when climbers are weak, tired and most vulnerable. So more often than not these fast and light pushes end without a summit and usually involve some epic descent from their high point. But, these climbers live to climb another day. Because years in the mountains have taught them how far they can push and when to abandon the mission. I’ve experienced these successes and failures multiple times so even 20+ years later it’s hard to take on a new adventure without evaluating these factors. And even though this run is on a much smaller scale, the same rules apply: I need to still have enough energy at the summit to spend 3-4 hours descending to 11,000 feet and the van. And I can’t be all wobbly and in minimal control on this tricky terrain. To compound the difficulty, I also anticipate that I will be doing much of this descent in the dark, even with a midnight start of the run.

How Long Do I Expect This Route to Take?

Well, If I just walked up this route at a leisurely pace for 2 days with the proper gear for an overnight stay then this would not be all that tricky. My plan though it set a reasonably fast time on this ascent so that the next person attempting it will need to be extremely fit, good at ultra-distance running and a very good hill runner to beat the time by more than an hour or so. Basically, I would like to throw down the gauntlet and invite people to go for this adventure run. Of course, there are likely dozens of ultra-runners in Hawaii that if they wanted the FKT (Fastest Known Time) for this route bad enough they could likely take it. Obviously, one of the goals of my Sea to Summit runs though is to put in everyone’s’ heads that these amazing adventures are right here in our backyard and they should go and do them. No Buckle. No medal. No aid stations. No crowds. Just you finding your limits while communing with our island.

If the route is actually 53 miles long with 14,071 feet of vertical gain then a great time for me would be 17 hours. A good time would be 19 hours. These times, of course, are for doing the run with zero acclimatization.

How Do I Come Up With Those Numbers?

Often people ask me how I figure out what I think my time will be. Below I try to spell out my basic formula.

Previous Training Run Results

Bottom Section: 4:55:43 @ 13:26min/mile pace @ 149bpm (22.0 miles | 4,150 feet gain)

Middle Section: 5:55:27 @ 18:23min/mile pace @ 145bpm (19.3 miles | 6,403 feet gain)

Top Section: 5:31:06 @ 28:53min/mile pace @ 135bpm (11.5 miles | 3,518 feet gain)

From the above, if I add them all together I get 16:22:16 @ 18:36 min/mile pace with an average HR of 143bpm covering 52.8 miles and 14,071 feet of gain. Now I consider that all of these runs I went into tired from the week of training before it. So they are in no way the fastest I could cover these miles. But they are close to what I might intelligently pace myself for 12 to 14 hours of running. I can see my heart rates were a little high for the bottom section and likely I need my overall heart rate to average near 135bpm to get my best effort for over 16 hours. This means I would need to back off the paces I ran in the bottom and middle section. How much water and extra gear am I carrying at any time? Is it rainy and windy or smoking hot? How long are my rest stops? You can see this gets pretty complicated. What I will do though is expect that I will be well rested and the day will be rainy, wet and low visibility for most of the run. So if all my workouts went according to plan (they did) and I paced myself well but not too hard (I did) I can run a basic formula to guestimate my time. So if I am being competitive add 7% more (+68 minutes). If I am being conservative then 20% more (+196 min). This means my fast time would be around 17:30 and my conservative time would be around 19:40.

So many things can change to totally wreck all my predictions. Yet barring something physically going wrong with me or a snow storm I can predict that even if it rained all day and I was in a dense fog for some of the time I would still fall close to those numbers. Honestly all the above is really most important though for my family who is following my progress – primarily Karen my wife. She needs 1 semi-firm time: When to pick me up at the Mauna Loa Observatory after I have descended from the summit. If I get out of the Mauna Loa Lookout by 8:15 am I can guess my best (optimistic) time to the summit at 5:00 pm and worst at 7:30 pm. With sunset at 7:04 pm and the knowledge it is way slower in the dark by headlamp I can expect 3 to 4 hours to descend. So barring any accidents on the descent I will be at the van with Karen between 8 pm and 11:30 pm that evening.

How to Track Me

Luckily Karen will be following a satellite tracker that I will be carrying. So if for some reason I am going faster or slower than my predicted times she will know. I will be sharing that tracking with all of you here on my Live Tracking Page. I will also try and share my Garmin 935 watch’s tracking which is dependent on a cellular connection (which will be spotty at best). This tracking has much better data like heart rate, pace, elevation gain (but buggy), and splits for each mile. I’ll be trying to post this link to my facebook page when I start the run.

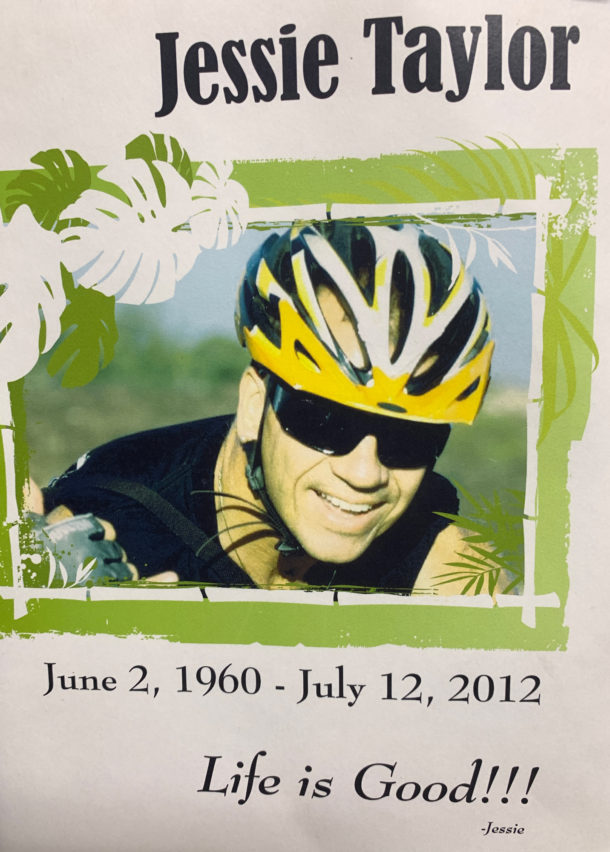

For Jessie Taylor

One final Note: In a way, I won’t be doing this run alone. On July 12, 2012, my good friend Jessie Taylor was hit by a car and killed while riding his bike around the island. For almost 7 years I have kept his ashes on my bookshelf waiting for a big enough adventure worthy of taking him on and spreading his ashes – and this is the one. Jessie loved endurance sport, adventure, good food, great friends, and especially his wife Carol Wolcott. At the ocean, I’ll scatter some of him. At the crater rim of the Kilauea Summit Caldera (and Halema’uma’u), I’ll do it again. And finally, at the summit, I’ll be sure to send the rest of him into the island breeze. So maybe this isn’t really a self-supported run. Maybe it’s a Jessie-Supported run. At least I’d like to think so.

Leave a reply